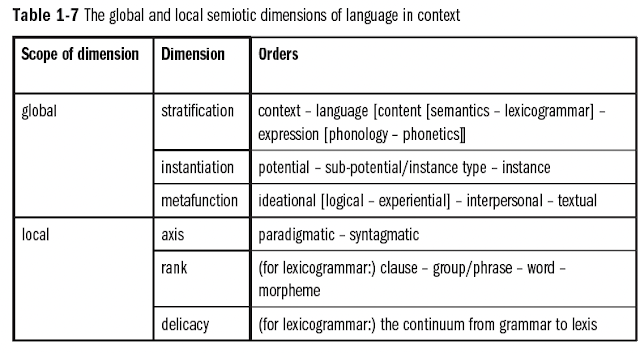

Phonology and lexicogrammar are treated as different levels of abstraction, with phonological oppositions realising lexicogrammatical ones. The Danish linguist Hjelmslev (1961) referred to these levels of languages as the expression plane and content plane, respectively.In the model of stratification assumed here, Hjelmlsev’s content plane is itself modelled as a stratified system, with discourse semantics realised through lexicogrammar. This makes it possible to entertain the possibility that [hopefully next time I will get my hair colour back ] was in fact negotiated in conversation as a request for goods and services rather that an offer of information. … What is significant here is that even though the first move is grammatically declarative, its speech function is negotiated as one we might normally associate with an imperative clause (a clause such as Get some of my hair dye from Target for me, will you?, for example).

(16)

So hopefully next time I will get my hair colour back.

— OK, I’ll go to Target for you.

The process whereby the content plane makes meaning on two levels, one symbolising the other, is referred to in SFL as grammatical metaphor (Halliday, 1985). The grammatical metaphor in (16) is an interpersonal one, with declarative mood symbolising a command.

Blogger Comments:

[1] This misleading because it is not true. Hjelmslev modelled semiotic systems in terms of content and expression planes. Halliday stratified Hjelmslev's content plane into semantics and lexicogrammar.

[2] To be clear, the 'model of stratification assumed here' is Halliday's, with Halliday's 'semantics' rebranded as Martin's 'discourse semantics'. For the theoretical shortcomings of Martin's discourse semantics, see here (English Text 1992) and here (Working With Discourse 2007).

[3] This deliberately misleads the intended readership of this section: those unfamiliar with SFL Theory. It is not Martin's derived model of stratification, but Halliday's original model that provided the system of SPEECH FUNCTION and its metaphorical realisation in the grammatical system of MOOD.

[4] To be clear, this text is from a monologue in which there is no conversation and no negotiation. The data can be viewed here.

[5] To be clear, in the system of SPEECH FUNCTION, commodities, goods–&–services and information, are either demanded of given, not requested or offered. An offer is the giving of goods–&–services.